special report||

Last week, Kabir Suman, one of Bengal’s most celebrated songwriters and political activists, found himself blocked from Facebook. He had written a song in support of the JNU students accused of sedition and posted it on his page on February 18; the lyrics contained the line “I am with you JNU”. “When I logged into Facebook a day later, I found that the post had been removed. A notification from Facebook said what I had uploaded was not in keeping with its guidelines and, thus, I had been blocked for 19 hours,” says Suman. He shakes his head in exasperation. “They would have probably banned our national anthem, too, had it been written now.”

Suman’s fears may not be altogether unfounded. Our national anthem, formed by the first five stanzas of the Bengali hymn Bharato bhagyo bidhata written by Rabindranath Tagore, found itself in the middle of a controversy for most of last year. In July 2015, Kalyan Singh, ex-chief minister of Uttar Pradesh and present governor of Rajasthan, demanded that a particular line in the anthem, Jana gana mana adhinayaka jaya he be replaced by Jana gana mana mangala jaya he. The line, the BJP leader said in a public function, was particularly offensive because adhinayaka refers to King George V of England.

This was not the first time that such an allegation was made. “My mother told me about an interview of Tagore she had read as a young girl. When Tagore was almost on his death bed, a senior journalist, Nanda Dulal Sengupta, interviewed him for a Bengali daily. Sengupta, who was known for his bluntness, asked if the adhinayaka in the song was King George V. Tagore remained silent for a few seconds. And then, he said that he wanted to strike down one of the songs he had written — Sarthok janam amar jonmechi ei deshe (I have achieved salvation by being born in this country),” says Suman.

If that were not enough, in a letter to Pulin Behari Sen on November 26, 1937, which was later published in Bichitra (p.709, Dec 1938), Tagore clarifies his stance: “That Lord of Destiny, that Reader of the Collective Mind of India, that Perennial Guide, could never be George V, George VI, or any other George”.

But who exactly is the adhinayaka invoked in the song? Abdul Kafi, assistant professor, Jadavpur University (JU), has an interesting take on it; he feels that adhinayaka is the collective will of Indians. “Though it’s open to interpretation. Some say he is invoking god, some say that adhinayaka is the collective will of the people. This song is all about inclusion and you will see Tagore is almost consciously listing out regions, cultures, ethnicities — he binds them all together. It celebrates humanism, it includes the people of the world even when it talks about the collective will of the world. In the following stanzas, he talks about the way humanity will wake up to a better tomorrow. He invokes the mother figure metaphorically to remind his countrymen about love and compassion,” says Kafi.

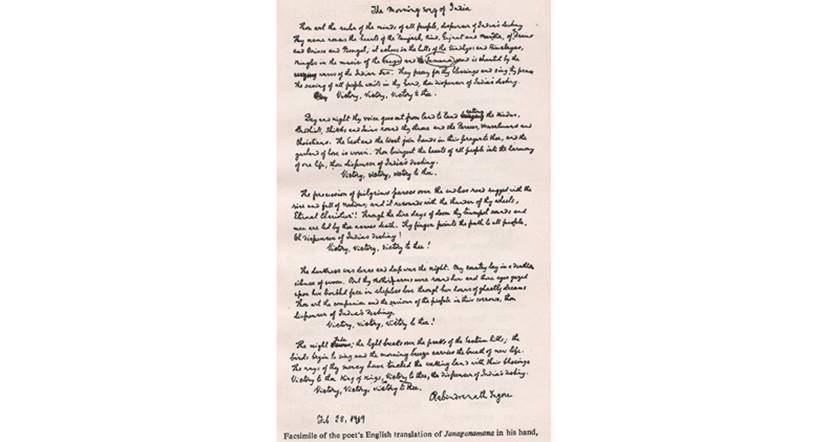

A fascimile of Tagore’s English translation of the Jana Gana Mana. Click on the image for a larger version.It’s an open secret that the Hindu Right has for long been against Tagore’s Jana Gana Mana, says JU professor Kunal Chattopadhyay. “Since the national anthem was adopted in 1950, Hindu nationalists within the Congress lobbied for Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Vande Mataram as the national anthem. Chattopadhyay, who was known to be a Hindu revivalist, was a figure of great importance for them,” says the professor of comparative literature and history.

A fascimile of Tagore’s English translation of the Jana Gana Mana. Click on the image for a larger version.It’s an open secret that the Hindu Right has for long been against Tagore’s Jana Gana Mana, says JU professor Kunal Chattopadhyay. “Since the national anthem was adopted in 1950, Hindu nationalists within the Congress lobbied for Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Vande Mataram as the national anthem. Chattopadhyay, who was known to be a Hindu revivalist, was a figure of great importance for them,” says the professor of comparative literature and history.

Tagore, himself, earned a lot of flak for his critique of Vande Mataram. In a letter written to Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose dated October 19, 1937, Tagore, while hailing Vande Mataram as a beautiful song in context to the novel it was written for, explains why it isn’t suitable for the Congress. “Tagore pointed out that Vande Mataram is essentially a hymn dedicated to goddess Durga. It celebrates Hinduism, which is not bad at all, but he felt that people from other religions might have problems with it.

And it was not fair to impose that on them,” says Kafi.

In her 2001 book, Hindu Wife, Hindu Nation: Community, Religion, Cultural Nationalism, Tanika Sarkar argues that Bankim’s novel Anandamath (1882), which contains Vande Mataram, prepares the ground for the transformation of Hindu cultural nationalism from an anti-British to an anti-Muslim focus, and points to ideological continuities between Bankim’s formulation and that of Sadhvi Rithambhara, the strident feminine voice of the Hindu Right a century later.

Tagore, who repeatedly questioned the concept of nationalism in his novels and essays, always prioritised “the ideals of humanity” over nationalism. “Even in Jana Gana Mana, we can see the expanse of his thoughts. It talks about humanity, not just petty borders. We also need to realise that Tagore would also have been the first person to invite discussion around any concept, be it of the nation or nationalism,” says poet and Tagore expert Shankha Ghosh.

This also means that Tagore’s ideals didn’t endorse blind allegiance to symbols. “Tagore wouldn’t have been bothered with the symbolic gesture of people standing for the national anthem. He would have probably been more concerned with the lawyers attacking students and journalists right outside a court,” says Suman.